In the October Country, the moon is perpetually full, enormous, and often partially obscured by sinister clouds and stark grasping tree branches. This has no effect on the majority of the lycanthropic population, but it does provide a beautiful ambience as we turn our attention to Universal’s first werewolf film, and indeed the first surviving werewolf talkie: Werewolf of London!

In 1935 Universal had pretty well established their brand, dominating the horror genre with their stable of high-quality literary monsters, and they’d just had a big hit with their first horror sequel, as we saw yesterday. By this point it must have occurred to people that they hadn’t yet done anything with a werewolf, although even before becoming a cinema icon the lycanthrope was a potent and popular myth. Two years earlier, Guy Endore’s novel The Werewolf of Paris came out and was very popular, and we can safely guess that Universal getting into the wolfman business within two years was no coincidence, especially in light of the similar titles. Universal did not adapt Endore’s book, though, possibly because of all the weird sex in it; werewolf BDSM was doubtless a factor in the novel’s popularity, but Universal had the Hays Code and state censorship boards to deal with.

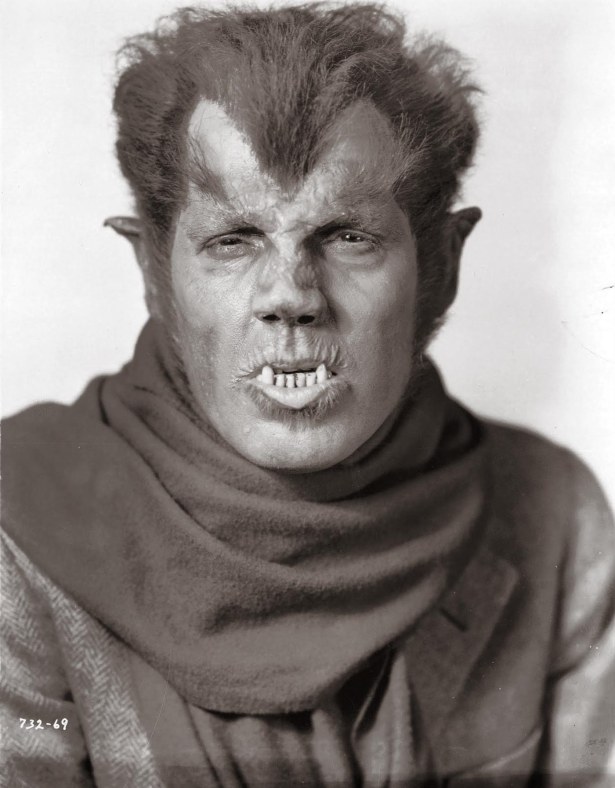

And so an original werewolf story was created, shaped by half a dozen credited writers and by director Stuart Walker, who has not come up yet in this series. Also unfamiliar to us will be the cast, for though Bela Lugosi was apparently the first choice for the supporting role of Dr. Yogami, he reportedly had other commitments at the time, and so this film features none of the mainstays we’ve come to expect from a Universal picture. Jack Pierce is still with us, though he was less than satisfied with the makeup he provided for the titular werewolf.

Without Lugosi or Karloff, we’re left in the hands of Henry Hull and Warner Oland; they both acquit themselves well. Henry Hull has a striking presence, lean, slighter than Karloff, with a hard sour-looking face. He’s Wilfred Glendon, botanist, and he’s in Tibet on a quest to find the Mariphasa, a fictional night-blooming plant that grows in the most isolated spot on earth: a Tibetan valley that mysteriously looks exactly like the spot in the Californian desert where Captain Kirk fought the Gorn. Their native guides refuse to go further, a European priest offers dire warnings, wolves howl, and some invisible force seems to actively restrain Glendon from entering the valley, but he’s a stubborn cuss, and so he persists, to his detriment, finding both the plant, and a bestial hominid of a somewhat lupine nature who pounces on him under the light of the full moon, taking a chunk of his arm but leaving him alive, and in possession of the fabled plant. We get our first look at Jack Pierce’s werewolf design, and it comes off pretty well.

What doesn’t come off so well is Wilfred Glendon, who’s another in an increasingly long line of obsessive scientists who neglect their significant others in favor of science. He is, to put it bluntly, kind of a terrible husband to his wife Lisa, even before his, ah, condition sets in. He’s distant, detached, and consumed with his work, but he’s also grimly possessive, which is on full display when his wife’s childhood friend Paul rolls into a garden party, and Glendon immediately goes even more stone-faced than usual.

Also at the party are a variety of carnivorous plants, some of them impressive puppet specimens, and a gentleman named Dr. Yogami, which gives us our first look at Warner Oland OR IS IT? (It is not).

Yogami is evidently intended to be Asian, possibly Tibetan. Here’s the thing, though: he’s played by a (very talented) Swede. Warner Oland was a prolific Swedish-American actor, but he had a somewhat Asian cast to his features, which he apparently attributed to some entirely unsubstantiated Mongol ancestors way back in his family line. Though he was hella white, Oland’s Hollywood career was mostly built on playing Asian characters, most notably Charlie Chan. He took that role very seriously, studying Chinese language, calligraphy, and culture, and he is a talented and very likeable actor, but he’s also, unfortunately, a giant in the field of yellowface, and that’s a whole thing.

Setting aside the unfortunate casting, though, our main concern with Yogami is that he immediately starts dropping heavy unsubtle hints that he was the werewolf who bit Glendon. Really, he might as well just come out and say “I’m a werewolf. I bit you, so you’re a werewolf now.” But he’s not quite so direct.

The infectious bite, incidentally, is original to this film, so far as I can tell. There are bits of folklore that may hint at it, but as a key element of a story, it’s unprecedented, at least so far as my research goes, and I refer you you to the header of this blog for my credentials in this field. This is also one of the earliest examples of the transformation being triggered by moonlight. Not the earliest, which I believe to be Robert E. Howard’s story “Wolfshead,” but certainly an early pioneer in spreading the concept that has now become ubiquitous. That leads to the first really superb sequence in the movie, for my money: when Glendon, messing with his moon-emulating spotlight in an attempt to get the Mariphasa to bloom, sees his wolf-bitten arm turn hairy when the simulated moonlight shines upon it. I’ve said before that black magic and mad science are the two sides of Universal’s horror coin: here’s a scene that marries the two, as a science fiction device triggers an ancient diabolic curse.

About that Mariphasa. Another innovation in this film is the plant that can cure, or at least treat, lycanthropy, a property sometimes attributed to wolfsbane in other films (shoutout to Ginger Snaps). This is what has drawn Yogami to London, since he wants that cure for himself. He does also warn Glendon about what’s coming, and the reasons he may also want to get in on that Mariphasa action: “The werewolf instinctively seeks to kill the thing it loves best.”

Glendon begins to feel strange. The hands get hairy. Light irritates his eyes. His cat is 100% done with him. He also kisses his wife with all the passion of a granite statue, but it seems like that’s just how Glendon rolls.

Then we get the second superb scene in the film, the bread and butter of every good werewolf flick: the transformation. Pierce wanted to do something hairier and more bestial, much closer to what Lon Chany Jr. would be wearing six years hence, but the makeup in this film actually looks pretty good, especially in this sequence, a diabolical mask with jutting fangs and shaggy sideburns and widow’s peak, pointed ears, heavy, bushy brows, and hairy clawed hands. He looks pretty savage, and the change from man to beast is accomplished beautifully, in a shot that sees him pass in front of a series of pillars in the foreground, emerging each time with more and more makeup on, with the sequence looking quite seamless.

It does rather spoil the effect when the werewolf pauses to put on a cap and inverness cape before heading out to rampage through London, though.

As previously mentioned, Glendon’s the jealous type, and he doesn’t seem to like his wife’s old friend Paul. This is unfortunate, as those two are currently at a party within sniffing range of the London Lycanthrope. He crashes the party, but inexplicably fails to do anything but alarm a drunk lady. He does finally manage to murder a woman elsewhere, though, conducting business more like Jack the Ripper than the Wolf Man. Really, this film has a lot more in common with Dr. Jekyll and Mister Hyde than Universal’s more successful subsequent crack at the werewolf mythos, and that resemblance to a recent successful film, Robert Mamoulian’s 1931 Jekyll and Hyde adaptation, may help explain why this movie was something of a flop.

The fact that the protagonist is pretty unlikeable can’t have helped the movie at the box office either. Henry Hull’s performance is good, but he’s playing a cold, unpleasant man. One thing that makes The Wolf Man work so well is Lon Chaney Jr.’s inherent warmth and lovability. Glendon here is an interesting character, but he’s nowhere near as easy to like or empathize with as Larry Talbot.

He does, at least, take some steps to mitigate the evident danger he poses to his wife. He does it by renting a room in the heart of London, which seems like a bad place for a werewolf to lay low, but it does put some distance between himself and the woman his other self is going to try and murder. Mostly this development serves to give us a too-long scene with a chatty gin-soaked landlady, which makes me miss both James Whale’s deft touch mixing humor and horror, and Una O’Connor’s genius for playing just that type of character.

But then we get the third superb sequence. “Please don’t let this happen to me,” Glendon prays, but it’s in vain, and some really brilliant makeup and lighting tricks, with a simple but skillful dissolve, make him seem to change again right before our eyes, and with a howl (a sound effect made by mixing Hull’s howl with the howl of a real wolf), the beast is loose, busting right out through the closed window and heading out to rampage.

His rampage continues to be more calculated lurking, rather than the running around ferally shredding anything in his path as a proper werewolf should, but he does at least put in some effort, and there’s a nifty shot where his victim sees his reflection in her compact mirror right before he strikes.

The next morning, Dr. Yogami and Paul Ames head out to warn the police about their werewolf situation and man, it is hard to get a handle on Yogami’s character. He’s a nice guy, he’s working on a cure, he keeps issuing vague and ominous warnings to try and get other characters to take action, but he also plays it coy, never coming out and telling anyone he’s a werewolf, not telling people about how Glendon is the werewolf and the guy responsible for these two murders, nor does he seem willing to take the extreme measures usually necessary to keep people like himself and Glendon from killing everyone they love. Ultimately, the only real cure for lycanthropy comes out of the bullet of a gun, as is well attested to in the vast majority of werewolf movies that came out after this one, but Yogami, despite being intimately familiar with the danger a werewolf represents, doesn’t seem to have any interest whatsoever in the final sanction for either himself or the monster he’s made of Glendon.

Oh yes, there’s also the matter of him stealing the Mariphasa blossoms for himself, ensuring that the unprepared Glendon will wolf out and go murdering in the moonlight. That’s a dick move.

Glendon, for his part, at least makes an effort, having himself locked up in a fortified medieval tower, leaving strict instructions that he’s not to be let out no matter what anyone hears from the other side of the door. Where he drops the ball is in his failure to double-check the structural integrity of the iron bars on the window, but at least he’s making an effort.

Those loose bars, combined with the unfortunately timed arrival of Mrs. Glendon and her old friend Paul, lead to another attempted rampage, but since Glendon continues to be a deeply unimpressive specimen of lycanthropy, he’s easily subdued by a walking stick. Paul recognizes the beast he thwarts as Glendon, goes to the police, then he and the police go to the scene of another werewolf murder from last night, and everybody finally starts connecting the dots. This is what I mean about Yogami being hard to get a handle on: despite being presented as a reluctant monster trying to fight the beast within, and despite having been a wolf for years at this point, he apparently took zero precautions to keep himself from murdering the shit out of the chambermaid in his hotel. That’s a degree of negligence that seems downright criminal.

All that’s a bunch of rather clumsy setup for what’s meant to be the show-stopping climax: a confrontation between two werewolves, mano a mano as the London bobbies race to the scene to save the imperiled damsel and all the other bystanders I don’t care about. And listen, there’s nothing, absolutely nothing, that I love more than a good werewolf fight. The only thing cooler than werewolf violence is werewolf on werewolf violence, my dudes, I believe that with all my heart. And they come so close, only to fail to deliver. Instead of the two moon-crossed scientists wolfing out and going at it tooth and claw in a savage orgy of bestial ferocity, we get Yogami swiping the last Mariphasa blossom to dose himself with it, which he does, thereby denying Glendon the means of escaping his transformation, denying the audience the sight of two werewolves at once, and also leaving Yogami in a face-to-face confrontation with an angry vengeful werewolf while he himself is stuck in his purely human form. And while Paul may have beaten the werewolf with a stick earlier, Human Yogami is not on that level, so he’s quickly dispatched. In the final analysis, I feel like Dr. Yogami might not actually be very smart.

It’s time to wrap things up, and the curtain falls with a very efficient conclusion. Glendon leaves the lab to pursue his wife, is briefly sidetracked by Paul, and is about to widow himself with the cops bust in and put a bullet into him. Not a silver bullet, we’re not there yet, and lead’s enough to put him down for good. Here’s another moment where this movie does shine, with Glendon getting some really solid last words:

“Thanks for the bullet. It was the only way. In a few moments now, I shall know why all of this had to be. Lisa, goodbye. Goodbye, Lisa. I’m sorry I couldn’t have made you…happier.”

Note that this regret applies not only to the stuff he did while under a supernatural curse that turned him into a feral murder-hungry beast-man, but also to all the various ways he was a bad husband before that. I do not know if that was intentional.

The police inspector on the scene declares that, as far as the official report is concerned, Wilfred Glendon was shot protecting his wife from an intruder, we cut to the open sky, and that’s that.

So here we have it: the first major werewolf movie, and it’s honestly something of a disappointment. What can we learn from it? What went wrong, and what went right?

For one thing, by this stage it’s hard not to imagine an alternate-universe version of this movie, with James Whale in the director’s chair, Karloff and Lugosi as Glendon and Yogami, and perhaps with Jack Pierce’s original creature design. I don’t think it’s a stretch to say that purely hypothetical movie would have been an improvement. Lugosi’s creepy intensity, Karloff’s solemn but very human persona, Whale’s skill at blending brutality and absurdity in a way that heightens both…I can also easily imagine a Whale-directed Werewolf of London doing something a little more interesting with the tense and complex dynamic between the two werewolves. If nothing else, the same subtle homoerotic edge you may see in Frankenstein and Pretorius’ relationship would have been compelling. And who knows, in that other universe, maybe Una O’Connor, my fave, plays the drunk landlady, which would have been ideal.

But that’s not the movie we got. What we have is frustrating, sometimes confounding, and in many ways, I think it’s safe to say, sort of a rough draft, a prototype that would be successfully iterated on six years later, with The Wolf Man. The werewolf isn’t wolfy enough. The protagonist is never someone I like or strongly empathize with. His antagonist never comes into focus, because he goes from being a rather sinister schemer to being the Van Helsing equivalent depending on which scene he’s in. The rest of the characters are forgettable, and while Valerie Hobson is charming enough with what she’s given to do, there’s not really anything to her. Which is weird, yeah? All the drama and emotion you could wring out of a story focusing on the werewolf’s wife, especially with the movie’s insistence that the beast wants to kill what the man loves, and yet that potential is ignored. A better version of the movie might have shifted to Lisa Glendon as our protagonist and point-of-view character, and made her a dynamic presence in the narrative.

Again, though, this is the movie we have. And within it, there is still much to like. The makeup isn’t what Pierce wanted, but it looks pretty great, and it’s a very unique design. The transformation sequences are rudimentary, but very superbly executed. Better, indeed, than what we see in The Wolf Man, though Frankenstein Meets the Wolf Man can’t be beat. The cast is good, even when the characters are lacking. There are striking images here, and seeds of the rich mythology that would soon blossom. This is the first movie about the werewolf’s relationship with the moon, the first movie about a humanoid bipedal wolfman, and the first movie to explore the connection between love and violence in lycanthropic context. The werewolf must kill what he loves, and as John Landis would articulate after internalizing all the Universal Wolf Man movies, a werewolf can only be killed by someone who really loves him. Or by some cop, in this case, but this is still a prototype.

So, it’s not the overlooked masterpiece I wish it was, but it is a crucial early step in werewolf cinema. Without this movie, we don’t get The Wolf Man, and without The Wolf Man, we don’t get literally every other werewolf movie ever made. Not a bad legacy, for an imperfect creature.

One thought on “The October Country Report #8: Werewolf of London”